Lithuania Failed the Migration Policy Exam

A tough policy toward migrants and refugees is reducing Lithuania’s integration outcomes, investment attractiveness, and competitiveness within the European Union.

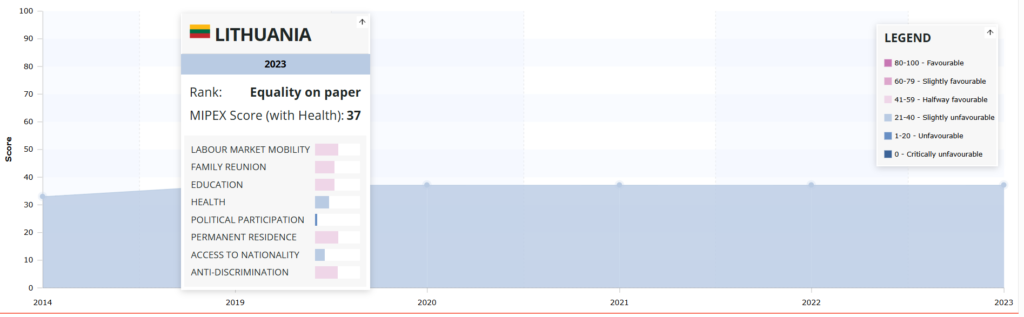

Lithuania has ranked second from last in the EU in terms of the quality of its migration policy. This was reported by MIPEX (the Migrant Integration Policy Index), an international tool used to measure and compare migrant integration policies across countries, including those in the European Union. Only Latvia performs worse than Lithuania when it comes to migrant integration and access to services.

Previously, to pass a driving test in Lithuania, one needed to score at least 80%.

Now, one must forget their native language and urgently learn one of the EU languages—because translation from other languages during the exam in Lithuania is prohibited.

If we approach this without double standards, Lithuania itself has failed the exam. On average, it scored 37 points out of 100, and on some indicators received results comparable to a “fail.”

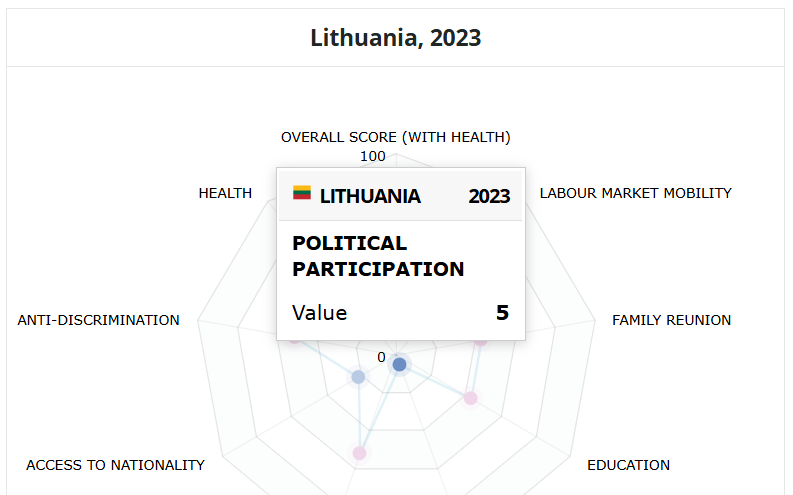

The MIPEX index evaluates how well state rules and programs help migrants participate in society on an equal footing with the local population. For Lithuania, the following areas were particularly highlighted:

- Political participation of migrants – 5 points out of 100;

- Migrants’ access to healthcare – 31 points out of 100;

- Access to citizenship – 22 points out of 100.

Even family reunification in Lithuania is a non-trivial task, judging by a weak 43 points—less than half of the possible score (another failed exam).

These data were presented in Brussels by Dr. B. Yavçan, who also presented the study.

Lithuania was mentioned in particular:

“There is demand for highly qualified migrants in Lithuania,” said Dr. Başak Yavçan.

However, even these seemingly obvious words are contradicted by Lithuanian statistics.

Let us examine this using the example of work with Belarusian migrants.

It is difficult to imagine a more qualified migrant than an IT professional. Yet over the past three years, Lithuania’s actions have been aimed primarily at pushing any Belarusians out of the country, without distinguishing between different levels of qualification.

Belarusians in Lithuania actually lead in terms of the number of highly qualified specialists: they account for more than 60% of all Blue Card holders—a special residence permit dependent precisely on high qualifications and salary level. These are mainly programmers and other IT professionals. At the same time, according to migration statistics, Lithuania loses about 7% of such specialists every six months. Compared with the overall outflow of Belarusians with residence permits at 8.5%, the difference is negligible. It is clear that Lithuania makes no distinction between migrants and refugees from Belarus based on their level of qualification—it fights everyone indiscriminately.

So why is Lithuania losing migrants of all kinds, including qualified Belarusians?

Every spring, again and again, Lithuania adopts a law on the persecution of Belarusians based on citizenship. And just before the New Year holidays of 2025–26, the Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs decided to extend these persecutions for two full years—from the beginning of 2026 through the end of 2027.

The repressive measures introduced by this law include:

- Bans on issuing visas and residence permits to Belarusians (which explains, for example, the low ranking in family reunification): since 2022–2023, Lithuania has suspended the acceptance of applications for Schengen and national visas from Belarusian citizens.

- Sanctions / freezing of assets: the law grants the government the right to freeze financial assets and economic resources of Belarusian citizens on Lithuanian territory. As a result, no reasonable business with migrant roots will keep its assets in Lithuania. Consequently, in 2025, foreign direct investment in Lithuania fell sixteenfold in one year—from €239 million to €15 million.

We also see absurd restrictions on Belarusian citizens that defy logic and common sense:

- a restriction on exporting euros from Lithuania (no more than €60 per person);

- a ban on importing any food products and alcohol into Lithuania;

- a ban on driving vehicles with Belarusian license plates if the driver does not have a Lithuanian residence permit, even though the Schengen Agreement states that a person who has legally entered the Schengen area may move freely within it—but not in Lithuania.

There are even more absurd decisions, for example:

In the same vein are the amendments to the Law on the Storage of Weapons, adopted by the Seimas (parliament) of Lithuania in December 2022, which prohibited Belarusians permanently residing in Lithuania from keeping weapons at home. As it later turned out, there were only 46 such Belarusians in the entire country. It is unlikely that these amendments were discussed in a single day; thus, 141 members of parliament spent several months and an unknown amount of taxpayers’ money simply to persecute and restrict access to weapons for just 46 Belarusians. Essentially, this is the size of one large family with distant relatives. This micro-level of state decision-making in Lithuania is, frankly, impressive and brings to mind Alexander Lukashenko, who travels around Belarusian collective farms personally counting cows.

Some amendments, incidentally, were not adopted—but they sound very characteristic: there was an intention, though not yet realized, to ban Belarusians from having digital signatures in Lithuania. Perhaps this is what saved Lithuania from last place—Latvia still managed to overtake Lithuania in violations of the rights of migrants and refugees in the MIPEX ranking.

It should be noted that all of the above restrictions are not mandatory EU rules but rather initiatives of certain local politicians with not very high qualifications. The low MIPEX rating is a direct consequence of Lithuania’s state policy toward refugees and migrants.